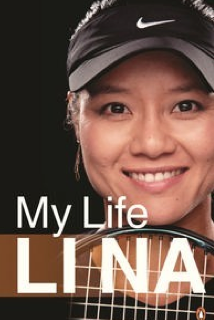

A long queue of fidgeting kids stretches back from the school’s door; kids whispering and giggling, intoxicated by the presence of fame. Tennis champion Li Na patiently autographs their tightly-clutched tennis balls, poses for photos and scrawls her name in book after book. Launching the English language version of her ghost-written autobiography ‘My Life’ in this massive private school in China’s capital of Beijing, Li is impressively easy-going with the kids who swarm around her. Several hundred, perhaps even a thousand, children have turned out to see and hear the Chinese tennis star, recently seeded three, the highest ranking ever for an Asian tennis player.

Sitting on a little stage in the school gym, under a giant poster of herself smiling on her book’s cover, Li Na tucks her long hair behind her ears and jokes with the kids. She took everything too seriously once, she says, so she started practicing her smile in the mirror, until it came naturally and spontaneously. “But still I don’t have a toothpaste sponsor.”

Three teenaged girls sit on the stage with her and ask piercing questions in both English and Mandarin about her inspiration and motivation, her past coaches, and the rose tattoo on her chest. Other interrogators, from the crowded ranks of cross-legged kids on the floor, pipe up with almost inaudible questions on how many hours a day she spends training (“six”) and her plans for the US Open this year (it’s already been played but she discusses her plans for next year).

Three teenaged girls sit on the stage with her and ask piercing questions in both English and Mandarin about her inspiration and motivation, her past coaches, and the rose tattoo on her chest. Other interrogators, from the crowded ranks of cross-legged kids on the floor, pipe up with almost inaudible questions on how many hours a day she spends training (“six”) and her plans for the US Open this year (it’s already been played but she discusses her plans for next year).

Wearing dark trousers and lime-green high-top sneakers, with turquoise fingernails and an earring in the front nubbin part of her ear, Li walks with a bounce. A force of controlled and almost casual energy, she is waiting to be unleashed on the Australian Open in Melbourne next month.

Now 31, Li is from the city of Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province in central China. A late bloomer in the tennis world, she won her first major in 2011, battling her way to victory in the French Open and making history as the first Chinese woman ever to win a singles Grand Slam title. More than 116 million Chinese viewers tuned in to watch that win on television, and the success enjoyed by Li and other Chinese women players has driven the nation’s surging interest in the sport.

When Li was a child, tennis was almost unknown in China. Li had never seen it played and hadn’t ever heard of the game when she was first asked to start training. Her parents hadn’t come across tennis either; her father had hoped she would excel at badminton. But a tennis coach spied the child’s tennis potential and the eight-year-old was sent off to a specialist sport boarding school. Accustomed to the smooth surfaces of ping ping balls, her parents called tennis “fuzz ball”, but they hoped Li would do well in this strange new sport.

Playing tennis became a test of her endurance and tenacity. As she recounts in her autobiography (published by Penguin), an early coach treated her monstrously, calling her “stupid” and “lazy”, yelling “are you a pig”, and making her run laps as punishment. Her home-town of Wuhan, too, was no picnic for aspiring sports stars who have to train outdoors. Known as the “oven city” in China, it alternately bakes in the summer and freezes in the winter and Li’s coach pushed the players hard, whatever the weather. “It was really tough,” Li now remembers, managing not to sound bitter. “For ten years, it was always things about how I’m stupid. I’m never smart enough and especially when we didn’t win the tournament, for sure the next day, she would come to the tennis court and she would say, ‘Why are you so lazy, you didn’t win the tournament?’ But even if I won the tournament, she would say ‘you have to train harder’. ‘Are you sure you can win the next tournament?’ So she always gave us a lot of pressure.”

As a child, Li responded to the pressure, honing her skills and winning more and more often, going on to rack up a long list of titles and championships. Yet the barrage of early criticism left her with deep-seated insecurity, and as adult player she sometimes simply couldn’t bear to lose. Defeats could leave her sobbing and determined to screw herself up tighter and tighter to ensure a win the next time. When the pressure got too much, she sometimes exploded – once shouting “shut up” (in English) at the audience, a lapse that did her no favours in China, and sometimes yelling on court at her husband. These days she shrugs off the psychological trauma of those early years. “It’s not so bad. It made me stronger, mentally. I think now I can recover. A little bit. Of course, for the last two years I have been much, much better (emotionally). Before I would sometimes punish myself.”

Her current coach, Beijing-based Argentinian Carlos Rodriguez, has an entirely different approach. “They tried to teach you tennis in a very strict and dictatorial way, but that is not coaching. That’s why you don’t get the most important part of the coaching; to give you autonomy, to follow you, to guide you, to show you how to get the best of yourself.”

Best known for his long-term coaching of former World number one Justine Henin, Rodriguez points out that learning how to lose, while remaining emotionally strong, is a vitally important part of the game. “In tennis even when you win, you’re still losing points, still losing games.”

There were other forces feeding into Li’s hatred of losing. Her much-loved father died when she was 14. As an only child with a struggling working-class mother, she felt compelled to start winning prize money to help pay off the family debts. She did win, but the toll was building.

When she was 20, a hormone imbalance left her feeling drained and ill; unable to play well. Some of the officials around her wanted her to continue playing, if necessary with injections of hormones to keep her going. “To make sure that I could play in the upcoming Asian Games, the leader of the team said, ‘You just need to make sure that she has the injections’,” she writes in her book. “Hearing this froze the blood in my veins.”

It was too much. Li left an ‘application for retirement’ form on the desk in her dorm, weighted down with a tennis racket. She fled home, where her mother agreed she should not be forced into a pharmaceutical regimen.

Li eventually recovered, after a long course of Chinese medicine and taking a couple of years off to go to university and study journalism. “When I was at university I learned the news has to be 100 per cent sure, and the truth,” she says wryly. “But now, in journalism, not everyone does that”.

Still, the truth can emerge in reputable publications. The ‘hormone’ medication Li managed to bypass was misinterpreted recently in a lengthy New York Times article, which described the drugs as steroids. Discovering its error, the paper then printed a handsome retraction.

Accustomed to inaccuracies and rumours about her making their way into print, Li Na was impressed by the correction. “I like that one,” she says. “Really. Because I think everyone makes mistakes, same like tennis athletes. Everyone makes a double fault.”

In her book, Li gives much of the credit for her tennis success to her husband and long-term love, Jiang Shan. A top-tier tennis player in his time, Jiang retired six months before Li first hung up her racket to recover from her hormone problems and study at university. He went to university with her, taking his own degree and he has been an indivisible part of her life since then.

For a few years Jiang was her coach, but that didn’t work well for either her career or their marriage. It obviously still rankles that she has become known for yelling at her husband on court. Those outbursts, she insists, are just one side of the story. “Okay, I really have to say that one day has 24 hours. I’m on the court to play; this is only two hours that I can shout at him. Otherwise, I have to listen to what he says.”

If Jiang wants to advise Li now, he sends the suggestions through her coach, Carlos Rodriguez. If he did start telling her what to do again, she explains, she simply wouldn’t listen. Still, Jiang is essential to her well-being. She isn’t lonely during her long stints abroad when she has him by her side; he is her hitting partner and her closest companion. She plans to have their children as soon as she retires, a boy and a girl (permitted under Chinese law because both she and Jiang are only children), and settle down somewhere that suits them both.

It could be anywhere. Li has been a big earner by tennis standards, according to many reports raking in as much as US$18 million. As China’s top-ranked tennis player, her prize money has been dwarfed by her endorsements, which have brought in substantial rewards.

Her decision to fly solo has been handsomely rewarded. In 2008, after the Olympic Games, the Chinese Tennis Association announced that four Chinese players, including Li, could become independent if they wanted to. It was a major reform. Instead of relying on the state to organise her career, pay all her expenses and take 65 per cent of her earnings, Li could go it alone, choose her own coach, structure her own schedule, pay all her own expenses and forfeit only eight per cent of her income (and a match bonus of 12 per cent).

This autonomy wouldn’t suit everyone. “It’s better for me, but every athlete is different,” she says. “Two years ago I asked some players about it. And they said they wanted to stay in national team.”

Of course the national team coaches can force players into a rigorous training schedule, and push them to work ever-harder. Li doesn’t seem to need that external discipline; she can push herself. She guesses that she has missed training once, or maybe twice over the past year. “Different people have different standards for themselves. I don’t want to think back and then regret.”

Rodriguez has been pushing her to train hard, to run gruelling sprint sets, to do weight repetitions for upper body and core strength. The sprint sets, she says ruefully, half kill her. She tells Rodriguez that she has a troublesome knee. He responds by asking whether she wants to be number one or number two in the world or not.

Playing less often these days, Li is saving herself for the major tournaments. She was exhausted when the Australian Open rolled around in January, after a day of travelling from China, followed by nine matches in ten days in the Sydney International. Next month she is taking it easier, missing Sydney and giving herself a week to adjust to Melbourne’s climate and get ready for the Australian Open.

Li Na’s energy and commitment is helping drive burgeoning interest in tennis in China where the broadcast of the Australian Open reaches 100 million viewers (one-third of the total global audience of more than 300 million).

Craig Tiley, chief executive officer of Tennis Australia, says the Open drew 684,000 fans through the gates earlier this year, and the fastest growth in numbers was in the visitors from China. Understandable, then, that Li can do no wrong in Melbourne. “Li Na’s comments about the Australian Open her favourite, and feeling like it’s her home Slam is something that we cherish and don’t take lightly,” Tiley says.

Still, for all the times she has visited Sydney and Melbourne, Li has never seen the sights, never seen the Opera House or Sydney’s beaches or Melbourne’s bay. She has her eye on the prize and her visits usually only encompass getting ready to play tennis, playing tennis, and recovering from playing tennis.

She took some advice offered by long-time tennis champion Martina Navratilova. After Li won the French Open in 2011, Navratilova sought her out in the locker room, and explained that she now she was a Grand Slam champion, Li had to learn how to say no. ‘No’ to would-be friends. ‘No’ to everyone who wanted a piece of her. These days a professional agency looks after her refusals. No, it isn’t possible to watch Li training. No, it isn’t possible to set up another interview. No, it isn’t possible to extend her press time.

The French title opened many doors. “In the course of one year, I’d been crowed French Open champion, become a representative of women’s tennis in China, and signed a business contract worth more than 1 billion yuan,” she writes in her autobiography.

Although Li is older now, and some experts must think she is coming to the end of her long and successful career, she is still in form. Her difficult knee, which has been operated on three times and which still requires weekly injections (“like oil for the machine”) hasn’t troubled her too much since the beginning of 2010. She has a doctor and a physiotherapist on call in Munich, where she spends much of her time, and she is reaping the benefit of expert advice on her physical well-being. Playing in a controlled way for the past year, deploying her killer forehand and powerful backhand, Li Na is expected to produce some fireworks in the Rod Laver arena.

One-time champion player Sandon Stolle, who coached her and a few other Chinese women players before the Beijing Olympics, believes that everything is rolling into place for Li – for perhaps the first time. She has an experienced and thoughtful coach, she is limiting her schedule, she has the right people around her, she is playing consistently well and she has her emotions under control.

“The biggest change I’ve seen in the last couple of years is that she believes she can win,” Australian Stolle says. “She believes she’s supposed to be there now. The ability was always there, from a ball-striking point of view, but in her head, I don’t think she really believed she could do it.”

Now, in this echoing school in the massive metropolis of Beijing, Li smiles slightly as she thinks of the beckoning Australian Open and the chances of another Grand Slam title. She has won kudos and many admirers in Melbourne, where tennis fans like her skill, her effort, her honesty and her self-deprecating humour. She likes the weather, which she says reminds her of Wuhan, and she likes the respectful crowds, people who almost uniformly fall silent when ‘time’ is called. She has never won the Australian Open, but maybe she’s closing in on it.

“It’s been pretty close twice,” she says. “Especially this year, I’m feeling I really can catch that. Hopefully next month.”

She looks quizzically at a new photo of a bluer than blue Melbourne sky, where someone has a nice line in sky-writing: “I (heart) you li na (heart)” which may or not refer to the potential Australian Open winner.

“Is it photoshop?” she asks, grinning. “I love it.”

Additional reporting Jie Chen