It began with a few washes of clear blue water-colour on a white page. Evolving from this first simple splash of art, the design grew and developed. By late last year it was a sophisticated entry for the multi-stage international competition to design a massive municipal museum in northern China. By April the adventurous Australian concept, by Brisbane architects Cox Rayner, had won.

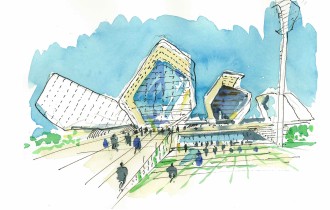

At 80,000 square metres, and with an estimated cost of $290 million, the museum is destined to be perhaps the largest Australian-architect designed edifice in mainland China. A clutch of five huge, shimmering white tubular pavilions stretching into Tianjin Bay, on the Chinese coast east of Beijing, the gleaming maritime museum will one day soon become a recognisable descendant of those very early sweeps of blue water-colour.

Architects at Cox Rayner in Brisbane barely stopped for a deep breath and a glass of champagne after their big win – deadlines loomed and work on the project accelerated. The firm’s principal, architect Michael Rayner, expects that construction on China’s first national maritime museum will begin in earnest next month. “It’s pretty fast, and it’s got to be completed by the end of 2016,” he says. “That’s lightning speed in our terms.”

Urban China is expanding at a breakneck pace, and with this municipal growth comes an inexhaustible demand for new municipal architecture; and it’s often interesting and expressive architecture.

The Australian-designed “Water Cube” in Beijing, constructed for the Olympics, has an exterior evoking giant bubbles. The National Stadium, also constructed for the Olympics, was at least partly designed by the dissident artist Ai Weiwei and the tangled structure is now widely known as the Bird’s Nest Stadium. Then there’s the World Financial Center in Shanghai, a soaring skyscraper with a bevelled tip, and the CCTV Tower in Beijing, once described as a “three-dimensional cranked loop” – both interpret geometry as an artform.

The Cox Rayner architects unleashed their creativity for the maritime museum design. “Certainly there was lots of encouragement to create a very abstract, expressionist building,” Rayner says of the multi-stage competition. “The final three were the most sculptural buildings that they chose to go forward, so that’s saying something.”

Rayner and his team presented a huge array of photographs and drawings to the Chinese judges to illustrate the idea that architecture can be interpretive, rather than simply replicating symbols. “We were trying to say if you look at the Sydney Opera House, or the Guggenheim Bilbao, they conjure up different images for different people,” Rayner says. The auspicious Chinese symbol of a jumping carp was discussed, also ships moored on a pier on a Chinese port, also Le Corbusier’s famous recurring “Open Hand” motif, which the French architect saw as a sign of peace and reconciliation.

Cox Rayner’s design efforts eventually paid off with the big win. But it was a gamble by the Queensland firm; a gamble that might easily have failed. Cox Rayner architects travelled to Tianjin maybe eight times while they were working on the competition submission, and put in an untold number of hours on the design. Rayner thinks the firm probably spent about half a million dollars on the two main stages of the competition. It was a big punt, for very big stakes.

Now the joint venture between Cox Rayner and the Tianjin Architecture and Design Institute has been awarded the commission to design and build the museum, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s all smooth sailing from here.

Chinese authorities are often remarkably adventurous, and the nation has offered scope for bold design – perhaps more scope than architects are generally afforded in the west. Yet there can be hazards lurking in this sea of seemingly endless architectural opportunity. China is notorious for intellectual property theft: fashion, technology, electronics, manufacturing – even designs by world-famous architects like Zaha Hadid – all routinely ripped off.

The various layers of Chinese government are unaccountable, the processes often opaque. China’s legal system is controlled by the ruling communist party. Criticism of the authorities is rapidly suppressed. Cultural misunderstandings are manifest in many international undertakings. China can be a difficult place to navigate, to say the least.

The Buchan Group, with a base in Fortitude Valley, is elbow-deep in several massive retail projects in China at the moment, in Dalian, Changsha, Tianjin, Nanjing, Chengdu and Shanghai. Director Phil Schoutrop has spent a lot of time in China, and he says the Buchan Group is working in collaboration with international architects on the projects. The massive malls, perhaps “twice the size of Chermside”, are within giant mixed-use retail, commercial and residential projects worth as much as $4 billion, and the Buchan Group is concentrating on the components of retail planning, interiors, graphic signage and design.

“We have an office in Shanghai,” Schoutrop says, “but our initial success in China has come about from doing projects for clients who are not based in China.” Huge challenges await those who work for Chinese developers, he warns, with differing expectations, drawn-out payment times and tangled bureaucratic red tape often marring the process.

For its part, ThomsonAdsett, led by the firm’s Brisbane-based chairman David Lane, has carved out a speciality niche designing seniors’ living and medical facilities in China. Nic Hughan, the firm’s managing director for south-east Asia/China, says the aging Chinese population presents a huge market for Australian architects. With 400 million elderly Chinese expected to need some form of assisted living or nursing care by 2030, the architecture possibilities are virtually endless.

The firm is currently working on a new seniors’ living community in Gongqing, south-west of Shanghai, the first of four similar projects. The plans are at the detailed design stage, and phase one has a budget in the order of 350 million renmimbi ($61 million). Hughan says it’s also likely that a design will be commissioned for a new private hospital, specialising in geronotology. Other projects are at the strategic planning level. “It’s a massive market; we’re unashamedly maintaining our specialist place in those disciplines,” says Hughan, who has lived in Beijing. “It’s probably the most buoyant market over there.”

Aware of the problems that can beset Australian architects in China, he says competitors in international design competitions sign over intellectual property rights, and Chinese developers can reserve the right to cherry-pick through the designs. Hughan has heard of one competition winner who was told to forget their winning design and use the runner-up scheme designed by ThomsonAdsett. Caution and care are the bywords for working in China he says, and ThomsonAdsett builds on existing relationships to ensure smooth cooperation and payment within reasonable timeframes. “Cold calls just don’t work.“

Noel Robinson, chairman and founder of the Queensland firm Noel Robinson Architects (NRARC), agrees that building solid relationships is crucial in China. A sister firm, EARC, has an office in Shenzhen, very near Hong Kong, and Robinson says the architects have been working on a substantial amount of master-planning, as well as designing a new yacht club. “There are huge difficulties (working in China), but there is also great scope,” he says. “It depends on the project; it depends on the people.”

The chief executive officer of the Australian Institute of Architects, David Parken, believes the pace of China’s urban expansion is “mind-boggling” and it offers vast room to move for Australian architects, but he has seen some of the knottier Chinese problems up close.

“As some of our members will tell you, sometimes you can win the design competition but lose the commission,” he says. “You get your first prize money and then you don’t end up being commissioned for the work because you can’t come to a contractual arrangement. That’s very disappointing. But that’s what can happen.” Issues of intellectual property theft can also blight dealings in China. Parken remembers the case of Australian architects operating in China who were congratulated on the new hotel they had designed. Great. Except they hadn’t designed it; some ex-employees had taken the firm’s name and used it – in Chinese – to brand their independent operation.

And, in China, Australian designers have to factor in some of the worst air-borne pollution in the world. The skyline of Beijing is often obscured by the particle-laden fug that renders the air almost unbreathable when the wind is blowing from the wrong quarter. The soot that descends from this dirty cloud settles on the city, a visible legacy of China’s rapid industralisation. In the face of this dirt, the Water Cube was designed to incorporate special ETFE (a flourine-based plastic) panels, which are self-cleaning at a molecular level, so that when it rains, they clean themselves. Unfortunately it doesn’t rain very often in Beijing, and the bubbles sometimes look dirty.

Tianjin, too, has enormous problems with air-borne pollution, despite enjoying coastal breezes. Rayner saw the soot layered on many of the city’s buildings, and he and his colleagues were concerned. “There is this rolling, shimmering white roof,” he says, describing the maritime museum design. “So we’ve been thinking about how how we do self-cleaning buildings; going into material research.” He and his colleagues originally wanted to use some kind of ceramic tile, but now they are proposing an enamelled metal tile which should be more soot-resistant. “I think the priority is going to be that this building should shimmer all the time and not look like a black cloud.”

Despite all these problems with deal-making opacity, with copyright issues, and with soot, a range of brave Australian architect firms are making the most of China’s massive urban expansion. Some have established offices in a number of the nation’s major cities – and it appears they are reaping the rewards.

The McKinsey management consulting firm predicts China will have at least 221 cities of more than one million people by 2025. And with this vast municipal growth comes an inexhaustible demand for new municipal architecture. One US academic, Jeffrey Johnson from Columbia University in New York, estimates that China is building at least 100 new municipal art galleries every year (an astonishing 395 in 2011). Commercial hubs are bulging, satellite cities merging, megapolises growing even bigger. Quickly.

Cox Rayner was wrong-footed by the extraordinary speed the Chinese authorities expected regarding the maritime museum construction. Toward the end of the design competition, as competitors fell by the wayside, the Australians began to understand that China wanted construction to begin almost immediately and to be completed within a couple of years. Startled, the Brisbane-based architects began to rethink even the way the structure would be completed. They considered elements that could be pre-fabricated, and sent by barge across the water to save time.

Even the building site was transformed as the competition progressed. “It was an interesting site issue, Rayner recalls. “It started out as a piece of water where they were going to reclaim the land to put the building, but at the time it was still water, so the schemes tended to work with the water. But about halfway through they reclaimed the land and built the seawall, so we all had to regather our thoughts.”

The Cox Rayner design was the only Australian entry in the final six – mostly from far afield, with designs from firms based in the US, in Spain, in China and in Germany.

The Australians were interested in the designs, and interested in the national cultural characters that seemed to shine through them. “The Spanish one, which was the one that got to the final three, was a very flourishing scheme, the German one was pretty clinical I guess, powerful but nevertheless clinical, the Americans’ tended to be more of a functional solution, I suppose,” Rayner remembers.

And, following on the theme of national characteristics, the Australian design included a great deal of water, around the pavilions and wending through them. “Things that are natural to us are not necessarily natural to others. I guess that’s when you say about this competition, being a maritime museum, living where we are, there’s this affinity with the water that we would try to work with, no matter what. With a maritime museum it’s much more meaningful.”