SOPHIE MAK will probably never go home. She has been too vocal and too critical of both China’s and Hong Kong’s governments over the years, using Twitter to comment on the unfolding tragedy in her homeland, Hong Kong. With long black hair, a short-sleeved, bright red dress and a surprisingly deep and husky voice, Mak, 24, is a typical Hongkonger: enthusiastic, committed to democracy, and deeply aware of the dangers threatening her home.

Sitting in the Kowloon Cafe in Sydney’s Chinatown, Mak chooses French toast – the waitress brings condensed milk to go with it, but Mak prefers maple syrup – and strong milk tea, also made with condensed milk. Spam also figures heavily on the menu of this resplendently Hongkongesque venue.

Many of the cafe’s patrons are keen for a taste of their home. Its traditional Chinese characters (different from China’s simplified system of writing) are on signs on the wall. The functional formica tables and stools tell a Hong Kong story, as does the music playing, which includes, Mak tells me, a protest pop song.

A cafe much like this one stood directly across the road from the apartment block where my husband and I lived, in Hong Kong’s middle-class Fortress Hill district, until the end of last year. The queue to get in often snaked around the block. But the easygoing residents of our very suburban district were happy to wait, clutching newspapers and umbrellas and chatting in Cantonese. Mak misses that life, those tastes and smells. The Hong Kong-style food she has found in Sydney just doesn’t match up, she says. “The food here is so much more expensive, and not nearly as authentic.”

Born and educated in the then largely autonomous city, Mak’s interest in politics was ignited by the democracy protests that erupted there in 2019. “That year was the turning point for me to not only pay more attention to Hong Kong politics but advocate more,” she says. “It’s very clear to me who’s in the wrong, who’s in the right. I can totally see how oppressive the government is in restricting freedom of speech and all that, freedom of protest.”

She’s one of the few Hongkongers I speak to who allows me to use her real name. She knows it gives her voice more weight. “It’s not like I can delete everything,” she shrugs, referring to her social-media criticism. “I don’t want to delete anything. I don’t want to be anonymous.”

Her Twitter account, which has more than 10,000 followers, tells the story. She’s tweeted about the “mass exodus” from Hong Kong, the “censorship” and the “draconian” national security law. In January last year she tweeted, “The government is brazenly purging the entire opposition camp and every last voice of dissent there is. It’s coming for everyone.”

These days, in the new Hong Kong, she could be prosecuted and jailed for her words. The likelihood of going home has dwindled to vanishing point, she says. “The more I do, in regards to human-rights associations, or with interviews even, it’s gotten even more unlikely.”

THERE HAD been disquiet in Hong Kong since 1997 when, after a century-and-a-half in control, Britain formally handed the colony back to China, with an agreement that it would retain a high degree of autonomy for 50 years. A Basic Law was introduced to protect freedom of assembly and freedom of speech and provide a certain level of universal suffrage for those five decades. It didn’t quite work out like that.

More than a million mainland Chinese people have moved to Hong Kong since the handover and locals claim that many of them have found plum government and corporate positions, inexorably altering the cul ture of the territory. Many homegrown companies, too, it’s widely thought, have been taken over by mainlanders. Locals had long quietly feared China’s encroachment, hoping to keep the worst at bay until at least 2047, and possibly beyond, given Hong Kong’s important position as a financial trading hub. But the crack- down came with lightning speed in 2020, and Hong Kong has suffered culturally and financially.

Protests were originally ignited in 2019 by the introduction of an extradition bill, which could have seen some of the territory’s criminal suspects whisked off to the mainland. The demonstrations rapidly built in size and fury until the day when an estimated 2 million marchers – a good quarter of the population – took to the streets.

Mak regularly demonstrated in those heady days, before coming to Australia in February 2020 to continue her University of Hong Kong arts/law degree at the Australian National University. By the time she finished the course a few months later, China, led by the increasingly authoritarian Xi Jinping, had crushed the protests with an extreme national security law. Formally called the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Safeguarding National Security in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, it was passed in

June by a committee of the National People’s Congress, bypassing the need for Hong Kong’s approval. It killed free speech and freedom of the press, undermined the rule of law, and transformed a once-freewheeling and bumptious society on the edge of China to a place of silence and fear.

From that day, repeating a political slogan could get a protester arrested. Writing a critical article. Singing a protest song. School textbooks with “sensitive” content were withdrawn from circulation. Newspaper editors were arrested and journalists fired. Publisher Jimmy Lai, a prominent Beijing critic and enthusiastic democracy supporter, was arrested in August 2020; despite having a British passport, he was determined to stay. He’s still locked up. His Apple Daily newspaper was forced to close and a million copies were printed of the last edition in June 2021: locals queued for hours to buy a copy.

Opposition politicians were jailed for months on end under the national security law – with no possibility of bail, and without being properly charged. In July 2020, police arrested eight protesters who held up blank placards at a gathering after the resistance phrase “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times” was banned. It’s now illegal to use that sequence of words in Hong Kong – the authorities consider it an “incitement to secession”.

Mak remembers sitting in an Airbnb apartment in Canberra on that chilly June day, watching the televised press conference introducing the security law on her laptop, and texting friends in Hong Kong on the encrypted messaging service, Telegram.

They were all horrified by the vague provisions in the new law that prohibit what’s defined as separatism, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with external forces. These elastic terms can encompass all manner of infractions and be punished by lengthy prison sentences, up to life. “It got me really scared,” Mak says. “Things that are said, things that are posted on social media, they can always use it against you afterwards.”

Mak has worked with Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International on various projects, including verifying videos alleging excessive police force in Hong Kong as genuine. These days a human rights advocate in exile, Mak misses her old life, the city’s busy streets, brightly lit until late at night, her friends and her family – and she doesn’t want to talk about them, worried about reprisals.

“I never planned to stay when I came here,” she says. “I was planning to leave in May [2020] after my exchange study ended.” She regrets not being able to say goodbye. She never had the chance for a farewell tour of her favourite places, for one last face-to-face talk with her friends; one final hug from her closest relatives.

Unable to go home, Mak is now working on her master’s degree in international security at the University of Sydney.

MY HUSBAND and I lived in Hong Kong for two-and-a- half years until late 2021, our second long stint in the city. I had spent a lot of time there as a child and as an adoles- cent, and I was fond of the energetic Cantonese people.

In 2019, I joined the massive protest marches, fled the tear gas and watched the city split along partisan lines. More than 10,000 protesters were arrested in those tumultuous months. The day the national security law was passed in 2020 was a day of melancholy. We knew Hong Kong would never be the same again.

Like Mak, I abandoned the city, but I knew long in advance that a departure was inevitable – I was an ex-patriate with a long history of dipping in and out of the territory. I hated Beijing’s inexorable takeover of Hong Kong’s freedom. We had lived in Jakarta and Bangkok for many years and spent a lot of time reporting from other variously dysfunctional Asian nations. Hong Kong had always seemed like an enclave of democratic values, where residents got cranky about everything from inadequate garbage removal to late buses, where its Independent Commission Against Corruption (set up in the 1970s under British rule) vigorously pursued misconduct, and newspapers published critical (and sometimes scurrilous) stories about government officials and business tycoons. Hongkongers had long experienced polite police officers, safe streets, a well-run and efficient city and the freedom to express themselves. From mid-2019, police were accused of using excessive force, streets often became a battlefield filled with smoke and shouting, the much-used MTR subway was repeatedly disrupted by demonstrators, and stations and lines were sometimes shut down by police to impede protests.

Then, in June 2020, the national security law pushed Hong Kong from fury to fear, crushing the city’s protests. Although it remained largely untouched by COVID-19 until early this year, the scourge provided the government with an excuse to ban social gatherings – which, of course, included protests.

DISMAYED BY the crackdown and the erosion of civil liberties, many thousands of Hongkongers made the painful decision to emigrate and start new lives abroad. The city’s airport became the backdrop for an ongoing procession of tearful farewells.

Hongkongers have flooded into the UK, which has flung open its doors, and to a lesser extent to Canada, the US and Australia. Last year, 104,000 people with British National (Overseas) status – those born there before the handover to China, and their dependants – applied to relocate to Britain. Closer to home, about 8800 temporary skilled, temporary graduate and student visa holders based in Australia became eligible for new permanent resident visas in a specialised stream that opened in March this year.

Hong Kong’s rigid pandemic rules contributed to the city’s massive upheaval. Hotel-room quarantine for up to three weeks – and the regular banning of flights from various airlines – kept residents effectively confined in the tiny territory. But late last year, COVID began to spread regardless. The public health system was rapidly overwhelmed.

With far less at stake than home-grown Hongkongers, many of the city’s shifting population of expatriates began to leave too, often despite a reluctance to ditch well-paid jobs and the cosmopolitan life.

On a more personal level, the law sounded a final death knell for me. Constrained by the pandemic, we continued to live in limbo

in our 30th-floor apartment in a no-frills block until the summer heat and terror politics drove us out. A friend’s spouse was locked up without bail for many months, no trial date set. Another friend, who had lived in Hong Kong for much of his adult life and who was an outspoken critic of China’s incursions, reluctantly and sorrowfully emigrated to Britain. Reading the local news became a depressing business; so much lost, so many locked up. We finally left for good last December, waving goodbye to the city from Hong Kong’s echoing, empty airport.

MAK, LIKE many of her compatriots who have recently settled in Australia, was keen to see Revolution of Our Times, a documentary about the Hong Kong protests. Hongkongers lined up for the premiere screening of the film at the Palace Norton cinema in Sydney’s Leichhardt in April. Cantonese chatter bubbled up as friends were greeted and seats were found.

Directed by Kiwi Chow, the emotional film is about the protesters – mostly young – who marched and organised, who communicated with each other via Telegram, who organised themselves into groups of medics, journalists, drivers and front-line “warriors”, who defended themselves with umbrellas, who picked up tear-gas canisters and hurled them back at the police, who threw Molotov cocktails, who occupied university campuses and who fought for their liberty and for their future for months on end.

As the credits rolled, applause rang out in the darkness and a lone voice called out in Cantonese: “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times.” As one, the Sydney audience echoed the words: “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times.”

Tickets to see the documentary in cinemas across Australia sold out at warp speed, fuelled by social media. More than 6500 had gone when the team decided to increase the number of screenings. And then it bumped it up again. And again. In Taiwan, the film won an award and broke a box- office record in its first week of screening. Mak saw the documentary in Sydney, and thought it a strong piece of filmmaking. She sat surrounded by Hongkongers, reliving those adrenaline-fuelled days. “A lot of people were weeping,” she says. “It was a powerful reminder of all the sacrifice.”

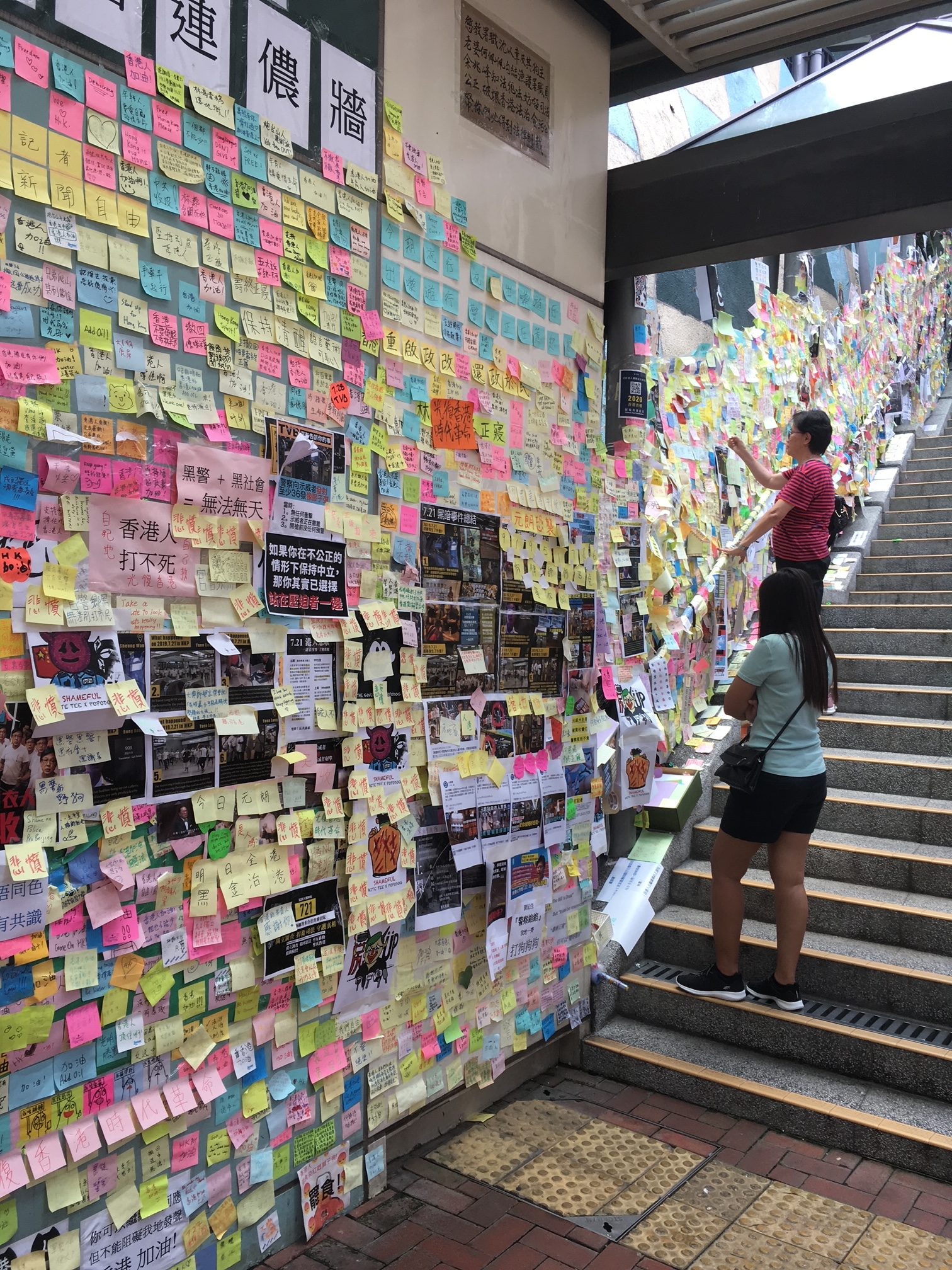

THE CLEVER and dogged protesters were always determined to make their point, mostly peacefully. In August 2019, tens of thousands joined hands to form an almost 50-kilometre-long human chain of resistance that wound through the city. One morning a month later, I noticed that the footpaths

leading to the Fortress Hill subway station had been completely covered with photocopies of a picture of the face of Junius Ho, a

much-disliked pro-Beijing legislator. Commuters had to tread on his face if they wanted to ride on the sub-way. Lines from China’s national anthem, such as “Arise ye who refuse to be slaves”, and quotes from Mao Tse Tung were co-opted for a different cause.

As time wound on many protesters were detained and locked up; many were beaten, many fled into exile. Some died by suicide. In early 2021, Beijing tried to stem the flood of emigration by withdrawing recognition of Hong Kong’s British National (Overseas) passports as valid documents, making it extremely difficult for many to withdraw their retirement money from the city’s mandatory pension system.

DANIEL CHAU* is nearly 60, but looks far younger, and wears a long-sleeved shirt, a vest and round- framed glasses. He says he was inspired by the Revolution documentary to do more to help Hongkongers fleeing their homeland. The scrapbooks he has brought to the nondescript cafe in Sydney’s northern suburbs where we meet tell a story of sorrow and remembrance. A lawyer by training, he is careful and circumspect, discussing the fire and passion of the desperate protests as a coffee machine burbles away in the background.

Like me, he and his wife arrived in Sydney at the end of last year. His elderly mother did not want to come with them to Australia; she couldn’t face the exhaustion of starting again in a strange land.

So now just Chau, his wife and their adult son and daughter live in Australia. “The reason we decided to come back is the political system is breaking down,” he says. “I’m a lawyer myself and I see the legal system in Hong Kong is seriously breaking down because it’s turning from the rule of law to the rule of man. It’s basically what the [Chinese] Communist government decides to do, the Hong Kong government follows suit.”

He first emigrated to Australia in the 1980s, returning to Hong Kong a decade or so later, lured by the economic reforms then underway in China and the hope that democracy was on the front foot across Asia.

Over the years, his disquiet slowly built. Then, in 2014, Hongkongers from the “umbrella movement” – so called for their chosen shield against police pepper-spray attacks – took to the streets to demand the right to have a say in choosing their leaders. Beijing, it had been decided, would effectively select the candidates for the position of Hong Kong chief executive, even though, according to the Basic Law, “the ultimate aim” was for that role to be filled by “universal suffrage upon nomination by a broadly representative nominating committee”.

Beijing proclaimed candidates for chief executive had to “love the country [China], and love Hong Kong”, and the promise of some degree of universal suffrage began to recede over the distant Chinese horizon.

I remember interviewing children (some still in school uniform) and passionate youngsters in their blockaded encampment on a stinkingly hot thoroughfare in central Hong Kong’s Admiralty district in 2014; we were surrounded by gleaming skyscrapers, at one of a number of protest sites. An hour in the relentless heat rising from the bitumen nearly killed me, but the protesters sat it out, coming and going as needs demanded, distributing bottles of water and singing solidarity songs. Some sat peacefully doing their homework.

I went back again and again; their determination remained undiminished. They stayed put for weeks, finally retreating in the face of increasing violence and sheer exhaustion.

Chau’s swirling fears for Hong Kong’s future began to coalesce with these protests in 2014 and firmed as time went on. “All this fear is realised now,” he says, adding that he feels cheated. He had returned to Hong Kong in the 1990s, comforted by the freedoms guaranteed in the “one country, two systems” policy agreed to by China. His trust was misplaced.

In 2019, with democracy protests in Hong Kong grow ing again and China’s grip tightening, Chau’s family, Australian citizens since their first time here, bought an apartment in northern Sydney – an escape route for when life in Hong Kong became unbearable.

THE PEOPLE of Hong Kong are almost always civil. During my time living there, I never saw a bar fight or a brawl. They are usually incredibly law-abiding – lost wallets are usually returned, cash intact, with the finders going to great lengths to track down the owners. It’s one of the safest cities in the world: I felt far safer walking the streets of Hong Kong than I ever have walking at night in Sydney. Hongkongers don’t push and shove; they even queue quietly to get on the subway.

But they hold their freedoms dear, and in 2019 and 2020 they demonstrated a rock-solid determination to hang on to their liberty. For this, many were happy to break the law. An estimated one million citizens took to the streets on June 9, 2019, a big slice of the city’s 7-million-plus population, many wearing white, marching to make their loyalties clear – they wanted no part of mainland rule.

I walked with them and their passion was evident. Their sheer weight of numbers was almost unstoppable, but the marchers were eventually met by police wielding batons and pepper spray.

A week later, they marched again, and this time as many as 2 million residents took to the streets, incensed by the police opposition and galvanised by the repression they feared was looming menacingly just over the horizon from the northern stronghold of Beijing.

We smiled and chatted as we shuffled along, the press of people preventing any show of speed or sudden movement. Many marchers were wearing black, mourning one of their own. The colour remained the favoured shade of protester wear for long months; eventually, the increasingly bellicose police were likely to stop and search any youngster seen wearing black.

Sophie Mak was somewhere in the press of regular marchers in the 2019 protests, as was Daniel Chau, appalled by the speed of the crackdown in Hong Kong.

By the day of the handover anniversary, on July 1, feelings were running high and a splinter group of furious protesters broke into Hong Kong’s parliament (known as LegCo) and spray-painted slogans on the walls. They retreated of their own accord, leaving money for drinks taken from vending machines.

“After the extradition bill we see police brutality, not rule of law, no due process, people arrested, people beaten up,” Chau says, remembering the turmoil. “The ammunition they were using was escalating in force. Tear gas, rubber bullets … people got hurt. They were using water cannons. Finally live ammunition; a youngster was shot on the street. So we thought, ‘We have to go; it’s time to go.’”

But the Chaus remained in Hong Kong, held back by family ties as the fury of 2019 spilled over into 2020. “That is a very difficult decision. My in-laws don’t want to go. My mum doesn’t want to go. They are old, they don’t want to go and live in a foreign place.”

The protests roiled on, diminished by the spectre of the pandemic and the consequent restrictions, but no less passionate.

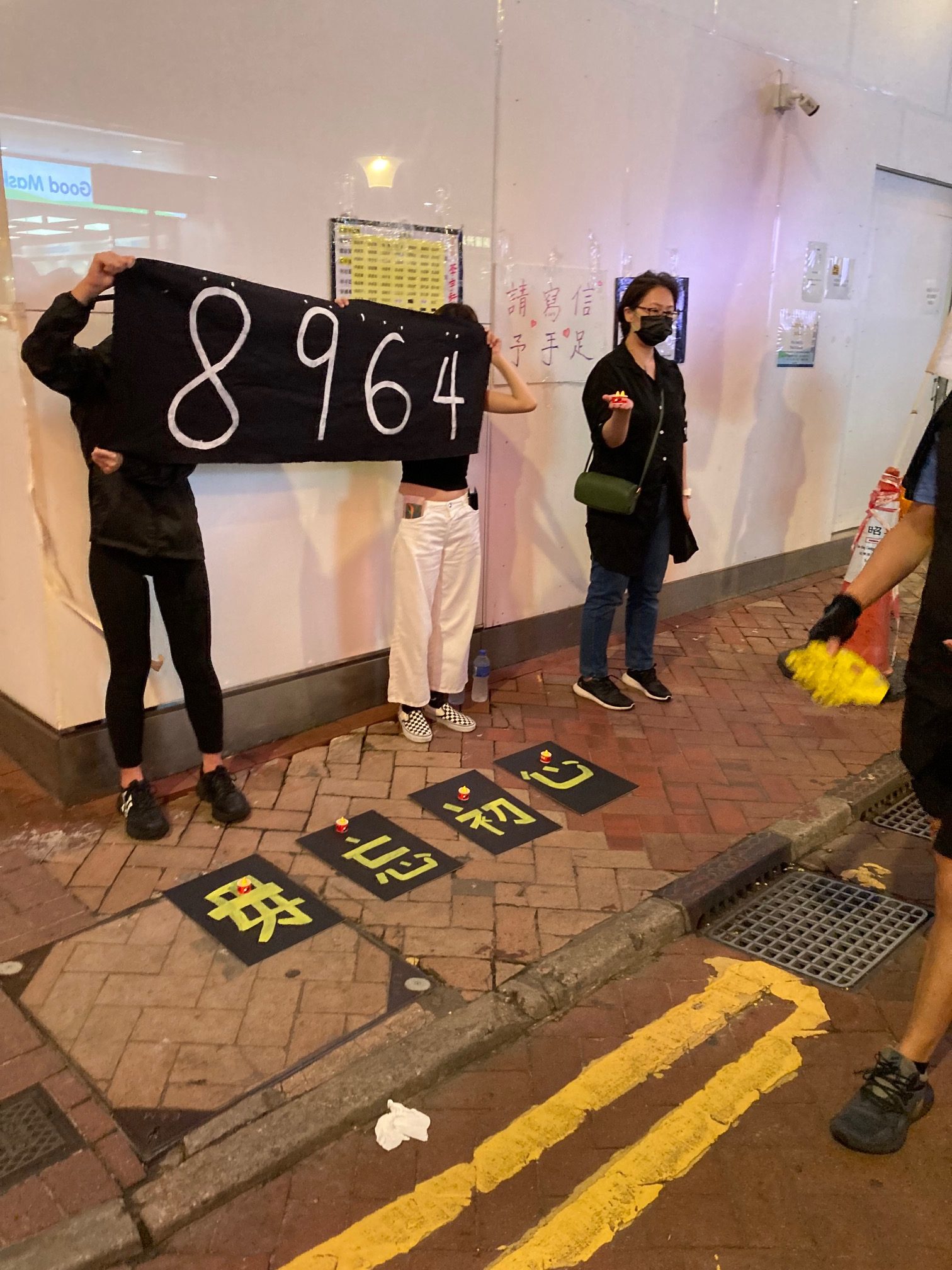

In early June, 2020, many thousands defied a government ban and gathered in Victoria Park for the city’s annual Tiananmen Square commemoration, the only one held anywhere in China. They turned up to remember the fallen of Tiananmen, and to underline Hong Kong’s independence from China.

I stood in the crowd that day, watching the massed bodies, the candles and the flowers, the masked faces, the passionate speeches, the sea of hands held up, fingers spread to indicate the protesters’ five demands: withdrawal of the extradition bill, an inquiry into alleged police brutality, the retraction of the “rioters” classification for protesters, amnesty for arrested protesters and universal suffrage. There was a warm feeling of shared hopes and aims. The locals who organised that event were later arrested.

A year later, in 2021, Tiananmen commemoration was all but dead, its spirit killed by fear of the national security law. Police officers roamed Victoria Park, much of it barred to pedestrians. I only saw a handful of protesters that day, including one elderly and undaunted woman known as Grandma Wong, wearing a face mask sporting Union Flags and marching across a street in nearby Causeway Bay, flanked by police officers.

A few of the courageous democracy activists who risked arrest in 2021 to commemorate the date of the Tiananmen Square uprising, June 4, 1989.

Brave youngsters stood on a footpath, masks on, eyes down, holding up a black banner with the date of the Tiananmen

uprising. One elderly woman in thongs, her face obscured by a large mask and sunglasses, held up a placard of newspaper cuttings with a photo of Tiananmen’s famed “Tank man”, a demonstrator who stood peacefully in the path of the tanks. Police roamed the streets, looking for malefactors, but by then, Hong Kong’s rebellious demonstrations had been almost entirely crushed.

The Chaus were dismayed by the introduction of the restrictive security law: it was another big push for them to leave Hong Kong. And yet they lingered. “To relocate a family is not that simple,” Chau says. “You have to prepare for assets to be relocated, funds to be transferred. Qualifications to be admitted. You have to prepare parents, so they accept one day you are going.”

The family has solid reasons to be wary of Communist China. Daniel Chau’s parents were born in Macau, then a Portuguese territory adjacent to China, and they migrated to Hong Kong in the 1960s. His uncle had a post in mainland China. During the terror years of the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards found a letter sent to this uncle by his sister, Chau’s mother, in Macau. They accused him of liaising with a foreign power – considered an appalling sin. His uncle took his own life to protect his family. “We know what the Communists can do, how crazy they can become,” Chau says.

His family, already split by the suicide, have been divided again by China’s takeover of Hong Kong more than 20 years too early. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has taken a toll.

“Most Hong Kong people don’t need independence,” he says. “Hong Kong people just want what was promised in the Basic Law. It was a social contract. ‘You promised us this; we decide to come here and work, and make this society prosper. You promised us. You cannot take it back after 20 years.’” He pauses and shakes his head. “I was naïve to believe in the promises of the CCP.”

Nathan Wong*, a 20-something finance student, was never an activist, but he joined a few marches in 2019 and was unhappy with the direction Hong Kong was taking. The protests grew and the crackdowns spread, and the idea of leaving Hong Kong became increasingly attractive.

He finally left in early 2020 after his family spent a month wrestling with difficult choices. “At the time everyone in Hong Kong was so depressed,” he says. “There was social injustice, the national security law. I have no regrets coming here.”

It took time for his parents to consider the circumstances and decide what was best for him and best for the family. Wong himself had few doubts. “Honestly, everything started with the extradition bill,” he says. “As a youngster, I didn’t see a future for myself in Hong Kong.”

In his immediate family, though, opinions have been divided. His parents, still in their birthplace of Hong Kong with his younger brother, continue to call it home. His businessman father has dealings with mainland China and was more supportive than Wong of both the Hong Kong and Chinese governments, and more concerned about the economic effect of the protests. “He had no problem with the extradition bill,” Wong says. His mother, a housewife, sympathised more with the protests, he says, but she was increasingly concerned about the potential impact of the unrest on her son. Eventually, a family consensus was reached and Wong was on a flight to Sydney. He expects to stay in Australia and that his parents, probably, will stay where they are.

Some Hong Kong families are united in sympathy for the protests, but are resigned to difficult geographic separations. A fresh-faced young woman in her early 20s with long hair and glasses, Vanessa Chan* expects the upheaval in her homeland to divide her family along generational lines, probably forever.

Like Wong, she left Hong Kong in 2020 to study here, and recently finished her health degree course at a regional university. Australia’s decision to provide a path to permanent residency has encouraged her to settle here, but she has had difficulty finding a permanent full-time job in her field where she lives and may have to uproot again and move to another Australian city.

Chan’s parents still live in Hong Kong and have encouraged both Chan and her sister, now in the US, to stay away, far from their home. They want Chan to remain in Australia and eventually have children here – grandchildren they’re likely to see only rarely. “They do not like the Chinese party,” she says. “They always said, ‘If you have a chance, just emigrate.’

“Me and most of my friends here have decided to stay, and we’re trying to figure a way to earn a living,” she says. “We just can’t imagine our future back in Hong Kong any more. So we’ve been trying to figure out another way to live our lives. And also for the next generation.

* Not their real names.

All photos by Sian Powell. Cover photo, Getty Images.